Summer reading lists are meant both for self-improvement and to impress an audience. That boy reading Proust on the beach has an eye for the girl nearby turning the pages of Virginia Woolf as much as he does for his own vow to get to the end of the damn thing at last. Presidential summer reading lists are no different, meant as much to titillate a particular public as to inventory a private disposition. When the President announces that he is reading, say, a new three-volume history of the Louisiana Purchase, he may actually be reading it, but he is also signalling to the commentariat watching from the next dune that it’s time for them to go into their “surprisingly thoughtful statesman” bit.

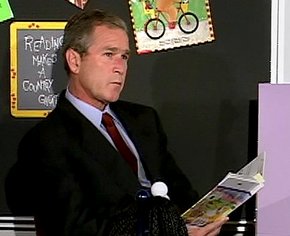

Summer reading lists are meant both for self-improvement and to impress an audience. That boy reading Proust on the beach has an eye for the girl nearby turning the pages of Virginia Woolf as much as he does for his own vow to get to the end of the damn thing at last. Presidential summer reading lists are no different, meant as much to titillate a particular public as to inventory a private disposition. When the President announces that he is reading, say, a new three-volume history of the Louisiana Purchase, he may actually be reading it, but he is also signalling to the commentariat watching from the next dune that it’s time for them to go into their “surprisingly thoughtful statesman” bit.Nonetheless, it is hard not to brood, in old-fashioned Kremlinological style, on the meanings of George W. Bush’s syllabus for this particular summer. Where in summers past he has read fiction by Tom Wolfe, or a comprehensive history of salt—both very good things in the right seasonal doses—this summer, perhaps under the pressure of events, he has embarked on a more strenuous list. An amazingly strenuous list, actually. It includes Albert Camus’s novel “The Stranger”; Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin’s book about Robert Oppenheimer and the invention of the atomic bomb; and Richard Carwardine’s new biography of Abraham Lincoln.

Already, it seems, the President has polished off the Camus and had a debate with his new press secretary, Tony Snow, on the origins of existentialism. Now, it’s possible to feel misgivings about the President’s ranch reading. Hasn’t there been, over the years, more useful material for him to scrutinize—memos, for instance, about Osama bin Laden’s intention to strike in the United States, or State Department studies on the difference between Sunnis and Shiites in a country he was about to invade? But it is the sunny optimism of humanism to imagine that books change lives, and that no one can come away from “The Stranger” entirely unaffected, particularly one who is, as he reminds us, a wartime President.

The book, after all, takes up the mysterious origins and horrific consequences of irrational acts of violence committed in the Arab world. Meursault, a French kid in Algeria caught up in a funk of alienation, shoots dead a stranger on the beach—a “native,” at that—for reasons he cannot explain even to himself. (He has had minor confrontations with Arabs, but Camus makes it plain that it hardly accounts for this act.) Camus’s purpose is to dramatize the psychology of pathological violence as a self-defining act, and his point, though open to debate with Tony Snow, is that violence may arise not as a result of premeditation and ideological fixation but as a sporadic and unplanned impulse, a kind of perpetual human temptation. To look too narrowly for rational purpose in it is to mistake its very nature. The freedom to act includes the freedom to do evil, and the murderer within us is no further away than a walk on the beach in a bad mood. People kill because they vaguely imagine, in a moral haze like the one overhanging the sun-scorched sand, that on the other side of murder lies some kind of expiation, or the thrill of rising above the mundane, or a way of pushing past alienation, or a shortcut to significance. People kill because they can.

How closely this truth touches the heart of this summer’s various horrors, or near-horrors. The bright young British Muslims, with their innocent-looking sports drinks, seem to have decided on mass murder not because they had exhausted all other possibilities but because, Meursault-like, in the madness of young men, it seemed thrilling and self-defining and glorifying—just as (the President might further reflect) the zeal of the neocon pamphleteers of summers past seems now to have come less from any strategic certainties than from the urge to some kind of muscular self-assertion, as wishfully defined as it was impossible to achieve.

Camus, the President should be reminded, did not come by this wisdom cheaply or at a distance; he came by it from the center of modern history. As “Camus at Combat,” a new collection of his editorials—he was a working journalist—makes plain, the experience, first, of the Nazi occupation of France, and then of the struggle of Algerian independence against France led him to conclude that the “primitive” impulse to kill and torture shared a taproot with the habit of abstraction, of thinking of other people as a class of entities. Camus was no pacifist, but he deplored the logic of thinking in categories. “We have witnessed lying, humiliation, killing, deportation and torture, and in each instance it was impossible to persuade the people who were doing these things not to do them, because they were sure of themselves and because there is no way of persuading an abstraction, or, to put it another way, the representative of an ideology,” he wrote. Terror makes fear, and fear stops thinking. The way out of Meursaultism is to think about particular people, proximate causes, and obtainable objectives—not an easy thing to do in any circumstance and nearly impossible in the face of those ideologies, left and right, for which, Camus writes, “fear is a method.”

And all this brings us no further than book one on the President’s stack, with Oppenheimer and Lincoln still to be chewed on. Bush may have emerged from his syllabus as little altered as most undergraduates emerge from theirs. Still, it is encouraging to think that he has spent the summer reflecting on the inscrutable origins of human violence and on the unimaginable destructive powers now available through American science, while contemplating the achievements of a great man who hated wars, made a necessary one, and wandered the halls of the White House agonized by the consequences. It sounds almost like the beginnings of wisdom, or, at least, a compulsory fall reading list for us all.

No comments:

Post a Comment