Contributors

Links

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

And What if Al-Qaeda Lights the Fuse?

Posted on Wed, Jan. 31, 2007

U.S.-Iran tensions could trigger war

JIM KRANE and ROBERT H. REID

Associated Press

BAGHDAD, Iraq - Citing Iranian involvement with Iraqi militias and Tehran's nuclear ambitions, the Bush administration has shifted to offense in its confrontation with Iran - building up the U.S. military in the Persian Gulf and promising more aggressive moves against Iranian operatives in Iraq and Lebanon.

The behind-the-scenes struggle between the two nations could explode into open warfare over a single misstep, analysts and U.S. military officials warn.

Iraq has become a proxy battleground between Washington and Tehran, which is challenging - at least rhetorically - America's dominance of the Gulf. That has worried even Iraq's U.S.-backed Shiite prime minister, who - in a reflection of Iraq's complexity - also has close ties to Iran.

Iran and the United States are already sparring on the ground.

On Jan. 20, militants kidnapped and killed four American soldiers in a raid in Karbala, and a fifth was killed in the firefight. A U.S. defense official said one possibility under study is that Iranian agents either executed or masterminded the attack, a suspicion based on the sophisticated and unusual methods used in the attack, including weapons and uniforms that may have been American.

He spoke on condition of anonymity because the probe is ongoing.

There has been speculation that the Karbala assault may have been in retaliation for the arrest of five Iranians by U.S. troops in northern Iraq.

Those five Iranians, who were arrested in the northern city of Irbil, included two members of an Iranian Revolutionary Guard force that provides weapons, training and other support to Shiite militants in the Middle East, U.S. Ambassador Zalmay Khalilzad said last week. Iraqi and Iranian officials maintain the five were diplomats.

Since the Karbala raid, U.S. saber-rattling has intensified. President Bush said this week that U.S. forces in Iraq would take action against Iranian operatives in the country, while insisting he had no intention of attacking Iran.

"If Iran escalates its military action in Iraq to the detriment of our troops and/or innocent Iraqi people, we will respond firmly," Bush told National Public Radio.

Although little evidence has been made public, U.S. officials have long insisted that Iran was supplying weapons and training to Shiite militias in Iraq, including some that have killed American troops.

The No. 2 U.S. general in Iraq told USA Today in an interview published Tuesday that Iran was supplying Iraqi Shiite militias with a variety of powerful weapons, including Katyusha rockets and armor-piercing rocket-propelled grenades.

"We have weapons that we know through serial numbers ... trace back to Iran," Lt. Gen. Raymond Odierno said.

The Air Force is considering more forceful patrols on the Iraqi side of the border with Iran to counter the smuggling of weapons and bomb supplies, the Los Angeles Times reported, citing senior Pentagon officials.

The U.S. is also building up its military presence in the Gulf in what it says is a show of strength directed at Iran. A second aircraft carrier is heading for the region, and Patriot missile batteries are being deployed.

Since Bush announced his new Iraq strategy in early January, Iranian officials have raised the alarm repeatedly that the U.S. intends to attack. President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad said Iran is "ready for anything" in its confrontation with the United States.

A newspaper close to Iran's supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei last week threatened retaliation for any U.S. military action - including stopping oil traffic through the Gulf's strategic Hormuz Straits and attacks on U.S. interests. The top editor of the Kayhan daily warned that Iran will turn the Middle East into "hell" for the United States and Israel if America attacks.

Iran expert Ray Takeyh said the risks are all the greater because Tehran has an "unhealthy" disregard for American power, which "enhances the prospect of a miscalculation."

Prof. Gary Sick, a leading authority on Iran, believes the U.S. is seeking to divert world attention from the crisis in Iraq and organize a coalition of Israel and conservative Sunni Arab states to confront Iran.

"I see this as a very dangerous long-term policy because it promotes the idea that Sunnis and Shiites should be distrustful of each other, and I think that could come back and bite us later on," he said.

Iran and the U.S. also are in dispute over Tehran's nuclear program. The United States accuses Iran of secretly developing atomic weapons - an allegation Tehran denies. Iran's defiant refusal to suspend uranium enrichment prompted the U.N. Security Council to impose limited economic sanctions.

The U.S. has also beefed up support for Lebanon's government in its power struggle with Hezbollah, the Shiite militia that Washington accuses of acting in Iran's interests.

But Lee Feinstein of the Council on Foreign Relations said the U.S. was finding it hard "to calibrate its message" to distinguish "between a stern message and a warning of attack."

The war of words has raised fears among both Democrats and Republicans in Congress that the United States and Iran are drifting toward armed conflict at a time when America is struggling against determined foes in Iraq and Afghanistan.

It has also unnerved the Iraqi government, many of whose members have close ties to Iran.

"We have told the Iranians and the Americans, `We know that you have a problem with each other but we're asking you, please, solve your problems outside of Iraq,'" Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, a Shiite, told CNN on Wednesday. "We do not want the American forces to take Iraq as a base to attack Iran ... we will not accept Iran using Iraq to attack American forces. But does this exist? It exists and I assure you it exists."

As the rhetoric grows more strident, a U.S. military official in the Gulf likened the U.S.-Iran standoff to the buildup in hostility in Europe before World War I, when the assassination of the heir to the Austrian throne triggered a tragic war that engulfed a continent.

"A mistake could be made and you could end up in something that neither side ever really wanted, and suddenly it's August 1914 all over again," the U.S. officer said on condition of anonymity, because of the sensitivity of the issue. "I really believe neither side wants a fight."

Iranian coast guard vessels recently veered into territorial waters on the Arab side of the Gulf, an event that could have been viewed as either a mistake or a provocation, the officer said. Both sides are on tenterhooks. "A boat crosses a line ... but what does it mean? You've got to be very careful about overreacting," the officer said.

Even if Iran pulled back from Iraq's conflict, it might not end the country's violence, said Kenneth M. Pollack, research director at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy.

"The truth is that Iraq is a mess. It is in a state of low-level civil war. And all of these groups are largely self-motivated," he said on the Council on Foreign Relations Web site. "But its much easier to blame it on the Iranians."

In Tehran, political analyst Hermidas Bavand said U.S. force increases were leading many Iranians to believe Washington is looking to pick a fight.

"It's an extremely dangerous situation," Bavand said. "I don't think Tehran wants war under any circumstances. But there might be an accidental event that could escalate into a large confrontation."

---

AP writer Jim Krane reported from Doha, Qatar.

© 2007 AP Wire and wire service sources. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.mercurynews.com

by Howard Zinn

Courage is in short supply in Washington, D.C. The realities of the Iraq War cry out for the overthrow of a government that is criminally responsible for death, mutilation, torture, humiliation, chaos. But all we hear in the nation’s capital, which is the source of those catastrophes, is a whimper from the Democratic Party, muttering and nattering about “unity” and “bipartisanship,” in a situation that calls for bold action to immediately reverse the present course.

These are the Democrats who were brought to power in November by an electorate fed up with the war, furious at the Bush Administration, and counting on the new majority in Congress to represent the voters. But if sanity is to be restored in our national policies, it can only come about by a great popular upheaval, pushing both Republicans and Democrats into compliance with the national will.

The Declaration of Independence, revered as a document but ignored as a guide to action, needs to be read from pulpits and podiums, on street corners and community radio stations throughout the nation. Its words, forgotten for over two centuries, need to become a call to action for the first time since it was read aloud to crowds in the early excited days of the American Revolution: “Whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it and institute new government.”

The “ends” referred to in the Declaration are the equal right of all to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” True, no government in the history of the nation has been faithful to those ends. Favors for the rich, neglect of the poor, massive violence in the interest of continental and world expansion—that is the persistent record of our government.

Still, there seems to be a special viciousness that accompanies the current assault on human rights, in this country and in the world. We have had repressive governments before, but none has legislated the end of habeas corpus, nor openly supported torture, nor declared the possibility of war without end. No government has so casually ignored the will of the people, affirmed the right of the President to ignore the Constitution, even to set aside laws passed by Congress.

The time is right, then, for a national campaign calling for the impeachment of President Bush and Vice President Cheney. Representative John Conyers, who held extensive hearings and introduced an impeachment resolution when the Republicans controlled Congress, is now head of the House Judiciary Committee and in a position to fight for such a resolution. He has apparently been silenced by his Democratic colleagues who throw out as nuggets of wisdom the usual political palaver about “realism” (while ignoring the realities staring them in the face) and politics being “the art of the possible” (while setting limits on what is possible).

I know I’m not the first to talk about impeachment. Indeed, judging by the public opinion polls, there are millions of Americans, indeed a majority of those polled, who declare themselves in favor if it is shown that the President lied us into war (a fact that is not debatable). There are at least a half-dozen books out on impeachment, and it’s been argued for eloquently by some of our finest journalists, John Nichols and Lewis Lapham among them. Indeed, an actual “indictment” has been drawn up by a former federal prosecutor, Elizabeth de la Vega, in a new book called United States v. George W. Bush et al, making a case, in devastating detail, to a fictional grand jury.

There is a logical next step in this development of an impeachment movement: the convening of “people’s impeachment hearings” all over the country. This is especially important given the timidity of the Democratic Party. Such hearings would bypass Congress, which is not representing the will of the people, and would constitute an inspiring example of grassroots democracy.

These hearings would be the contemporary equivalents of the unofficial gatherings that marked the resistance to the British Crown in the years leading up to the American Revolution. The story of the American Revolution is usually built around Lexington and Concord, around the battles and the Founding Fathers. What is forgotten is that the American colonists, unable to count on redress of their grievances from the official bodies of government, took matters into their own hands, even before the first battles of the Revolutionary War.

In 1772, town meetings in Massachusetts began setting up Committees of Correspondence, and the following year, such a committee was set up in Virginia. The first Continental Congress, beginning to meet in 1774, was a recognition that an extralegal body was necessary to represent the interests of the people. In 1774 and 1775, all through the colonies, parallel institutions were set up outside the official governmental bodies.

Throughout the nation’s history, the failure of government to deliver justice has led to the establishment of grassroots organizations, often ad hoc, dissolving after their purpose was fulfilled. For instance, after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, knowing that the national government could not be counted on to repeal the act, black and white anti-slavery groups organized to nullify the law by acts of civil disobedience. They held meetings, made plans, and set about rescuing escaped slaves who were in danger of being returned to their masters.

In the desperate economic conditions of 1933 and 1934, before the Roosevelt Administration was doing anything to help people in distress, local groups were formed all over the country to demand government action. Unemployed Councils came into being, tenants’ groups fought evictions, and hundreds of thousands of people in the country formed self-help organizations to exchange goods and services and enable people to survive.

More recently, we recall the peace groups of the 1980s, which sprang up in hundreds of communities all over the country, and provoked city councils and state legislatures to pass resolutions in favor of a freeze on nuclear weapons. And local organizations have succeeded in getting more than 400 city councils to take a stand against the Patriot Act.

Impeachment hearings all over the country could excite and energize the peace movement. They would make headlines, and could push reluctant members of Congress in both parties to do what the Constitution provides for and what the present circumstances demand: the impeachment and removal from office of George Bush and Dick Cheney. Simply raising the issue in hundreds of communities and Congressional districts would have a healthy effect, and would be a sign that democracy, despite all attempts to destroy it in this era of war, is still alive.

A Case for Impeachment

by Robert Scheer

Revelations in the perjury trial of Lewis “Scooter” Libby re-emphasize the need for an impeachment trial to establish the true story behind President Bush’s erroneous claim about Saddam Hussein’s supposed nuclear weapons program.

Marty Kaplan: The Founders Fumbled

"The system worked" is what so many of us breathed with relief when Nixon fled Washington in disgrace. What we told ourselves was that the country escaped its worst constitutional crisis ever because the Constitution contained within itself the mechanisms needed to overcome catastrophe. Looking at what's happening in Washington today, I can't help thinking that it's time to revisit that awe.

Fair Trade

by Thomas Geoghegan

What the left should offer business in order to revive the labor movement.

American Roulette

In our winner-take-all casino economy, the middle class is getting royally screwed. A call to arms for populism, before it’s too late.

Even Scalia Agrees

Why Would Congress Surrender?

By Fred Barbash

Wednesday, January 31, 2007; A15

In a matter of days the Senate is likely to begin debating several nonbinding resolutions on the president's plan for a troop buildup in Iraq. As the battle is joined, both houses of Congress need to be reminded that the stakes go well beyond this particular buildup, this particular war and even this particular presidency.

At issue is the constitutional law governing the war power of the executive branch, specifically the vastness of the "battlefield" over which President Bush claims inherent authority as commander in chief. Also at issue are all the comparable claims yet to be made by presidents yet unborn, armed with the precedents being set right now.

In these matters, there is no such thing as inaction. In a contest between two branches over separation of powers, silence speaks as powerfully as words.

That's because the Supreme Court rarely involves itself in disputes between Congress and the executive, expressly making it a two-way conversation -- a "shared elaboration" or "shared dialogue" in the words of scholars -- between the elected branches. When one branch drops out by failing to respond, the other branch effectively sets the precedent, which is passed along to the next generation and the generation after that.

Inaction, indeed, strengthens that precedent. Over time, inaction is taken as acquiescence, a form of approval, and the precedent becomes entrenched until it's as good as law.

This is precisely what has occurred over the years. Successive decades of congressional acquiescence in the face of executive claims of war power have allowed the law to be settled exclusively by the executive branch.

Now, people who know better show no surprise at the notion that Congress's only war-related authority is the power of the purse. Timid requests for legislative involvement are ridiculed and caricatured as "micromanagement" or, worse, as comforting the enemy.

It's as if there is nothing left to argue about -- except, of course, there is, though it seems so elementary.

Article II does indeed make the president commander in chief.

But Article I gives Congress not merely the power of the purse. It vests in the House and Senate the authority to "declare war," to "make rules concerning captures on land and water," to "provide for the common defense," to "raise and support Armies," and to "make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces." In addition, the Senate advises and consents on important military appointments, which is why Lt. Gen. David Petraeus was on Capitol Hill last week for confirmation as the general in command of U.S. forces in Iraq.

War is a shared responsibility. The records of the 1787 convention at which the Constitution was drafted unquestionably demonstrate that. An early version of Article I, for example, gave Congress the power to "make war."

The delegates changed the wording to "declare war," not to remove Congress from the process but to leave the commander in chief the "power to repel sudden attacks," as James Madison put it. "The executive should be able to repel and not to commence war," agreed Roger Sherman. In the eyes of some delegates, this limited authority was safe in the hands of a president because "no executive would ever make war but when the nation will support it," said delegate Pierce Butler.

One can argue about this view, of course, but Congress generally chooses not to, despite occasional prodding from Supreme Court justices such as Antonin Scalia. In a dissent in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, the 2004 decision requiring the administration to give detainees some neutral forum in which to make their case, Scalia noted that the Founders mistrusted military power "permanently at the executive's disposal."

"Many safeguards in the Constitution reflect these concerns," he said, including expressly involving Congress in the war-making function. Indeed, wrote Scalia, "except for the actual command of military forces, all authorization for their maintenance and all explicit authorization for their use is placed in the control of Congress under Article I, rather than the President under Article II."

Scalia also chided Congress for its "lassitude" on the topic. "Many think it not only inevitable but entirely proper that liberty give way to security in times of national crisis -- that, at the extremes of military exigency, inter arma silent leges," he wrote. "Whatever the general merits of the view that war silences law or modulates its voice, that view has no place in the interpretation and application of a Constitution designed precisely to confront war and, in a manner that accords with democratic principles, to accommodate it."

The equilibrium of government, in the view of the Constitution's Framers, rested on a stated assumption that each branch would fight fiercely to expand its authority but just as fiercely resist encroachment from another branch.

That Congress would refuse to fight seemed unimaginable.

The writer, who covered the Supreme Court for The Post, teaches at Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism. He has written widely about constitutional history.

The First Amendment: Good When You Can Get It

The First Amendment: Good When You Can Get It

by David Rovics

www.dissidentvoice.org

January 29, 2007

http://www.dissidentvoice.org/Jan07/Rovics29.htm

The organizers with United for Peace and Justice and all of those

participating have once again pulled off a giant protest march and rally. As

has happened every few months since the invasion of Afghanistan, hundreds of

thousands of people have converged for a national protest, this time in

Washington, DC.

The major media outlets decided this time that the protest was worth

covering. This time it was aired on CSPAN, reviewed by the New York Times,

the Chicago Tribune and the Houston Chronicle, and even recognized as the

socially diverse crowd that it was -- young and old, veteran activists and

first-time protesters, soccer moms and socialists.

As usual, crowd estimates given by the major media varied wildly from

"thousands" to "tens of thousands" to "just under 100,000." Some, including

the New York Times, dared mention one estimate of 400,000. This is

particularly notable since the NY Times was one of the many outlets guilty

of barely reporting on past protests, and frequently using vague terms like

"thousands" when reporting on crowds that had virtually filled Central Park.

I missed this rally, being on tour on the other side of the Atlantic this

time around. But looking at it from afar, it seems to have been a model

event. UFPJ was given a permit to have a march and a rally. The masses

descended, and the major media took note, at least to some degree reflecting

the reality that could be seen by anyone present -- that there are a lot of

people in the US against the war.

For people attending or reading about this weekend's anti-war protest, there

are certain assumptions that could be made, that the media also seems to be

confirming:

It may or may not make much difference, since democracy is mostly about

voting, but we have a First Amendment which guarantees freedom of speech and

freedom of assembly. When there's a really big national protest like this,

you will hear about it in the mass media.

Reading the corporate media over the years and listening to the government

spokespeople as well, certain other assumptions are clearly to be

understood:

If it wasn't reported, it must not have been very big or significant. If

there is any violence at a protest, it was probably started by protesters.

Protests are dangerous places with lots of angry people at them who

generally don't really understand what they're angry about. For some reason

because of the "war on terror," we have to have more police security at

protests since 9/11, since terrorists might target or take advantage of

otherwise non-terroristic protests. There is some kind of relationship

between protest and terror. As we know from our history books, since the

Civil Rights movement the authorities have learned from their violent

excesses in the past, and now when civilians commit acts of nonviolent civil

disobedience, they are gingerly carried off by the police. Police do not

attack nonviolent protesters without provocation.

Of course, all of these assumptions are false. For those of us who regularly

find ourselves on or near the front lines of dissent in the US, this is

obvious. But for every one of us like that, there are hundreds more

sympathizers. People like most of my extended family and I'll bet many of

yours, who are against the war, against much of what Bush stands for, but

they haven't quite made it to a protest or done much else to make their

views clear, at least not in several decades. Or if they have done

something, they've been one of the millions over the past several years who

have been to one protest, and not managed to get to another. So very likely

they don't have a very firm picture of what goes on out there in the land of

free expression.

CNN's polls have supported the notion for years that most of the country is

against the war and not supportive of the president. Yet most of the

protests are barely reported by CNN, if at all. And if they are reported,

they are rarely given the time necessary to show how the protest movement

truly represents civil society. If you weren't there, you probably wouldn't

know it happened.

And if you weren't involved somehow with the organizing of the event, you'd

be unlikely to know that the organizers were given a permit to march but not

to rally, or to rally but not to march, or were given no permit at all for

any central location. Or that the police were penning people into cages who

wished to protest. Or that many people were not even being allowed into the

cages in the first place.

Or that people committing acts of nonviolent civil disobedience, or in some

cases just walking down the sidewalk, were being tear-gassed, beaten with

clubs, shot with rubber bullets and electric tazer guns, crushed with

horses, held in unsanitary prison cells. That protest organizers' houses

were being raided by police, beaten bloody, computers and cameras stolen.

That spaces rented by protesters had been attacked by the police, with

everything inside the building being seized. That people were being attacked

frequently for the crime of riding bicycles in groups.

And that all of this had been going on under the false pretense of security

since long before 9/11.

I thought I'd recount some of my personal experiences with protest, speech

and the First Amendment over the past decade or so, as illustrations of how

things tend to go, in the hopes that some readers might find these stories

illuminating.

For those of us who come with what might be called the "radical narrative"

of history, it all starts with an understanding that democracy largely

happens in the streets, and that the rights we have only exist if we

continue to fight for them, otherwise they are taken away. It starts with

the understanding that the 20th century began with the authorities

brutalizing and arresting thousands of people every week for giving

pro-labor speeches on the sidewalk. With the criminalizing millions of

members of the IWW (the Industrial Workers of the World) by calling them

"German agents" because they called World War I a "bosses' war." Many

opponents of the war were jailed for years, including socialist leader

Eugene Victor Debs, who won a million votes for president of the US while in

prison for his anti-war views.

It starts with the historical understanding that we live in a class society

which operates under the golden rule -- those who have the gold make the

rules, and everybody else has to stand up for their rights by other means.

Those who have the gold declare the wars, consistently lie about the real

purpose of the war, and profit from the war. Those without the gold fight

and die in the wars.

It starts with the understanding, also, that the smooth operation of any

society requires that most people do not see history and reality this way.

That efforts will be made on the part of the powers-that-be to prevent this

from happening. And that if it seems this kind of awareness is spreading,

and manifesting itself on the streets, one frequent way to deal with this is

through disinformation or omission of information, and both subtle and overt

forms of repression.

February 15th, 2003 was an interesting case. Many of us already knew about

the imperial intentions of the US in Iraq, and didn't need to see the

disaster unfold before we knew invading Iraq was a terrible idea. The

protests worldwide involved many millions of people, including all over the

US. Half a million people, maybe more, were flooding into New York City. It

was a bitterly cold, windy winter day.

The NYPD had denied UFPJ a right to march. Citing security as a concern, the

police created pens for each block, to make sure it was impossible to march.

A block away from the pens, the police were sending thousands of people

walking dozens of blocks in order to then be turned away from entering the

rally area there. It seemed from my observation that perhaps half the people

trying to go to the rally weren't able to get in.

As with most of the major anti-war rallies in the past several years, most

of the people coming to the February 15th rally hadn't been to a protest

since the 60's, or ever. For those of us who had, the police behavior was

outrageous, but not surprising. For many of the well-dressed, middle-aged

folks from the suburbs or further afield coming in, the way the rally was

being controlled by the police was shocking, and many of them gave the cops

a good piece of their minds.

A year later the NYPD this time prevented organizers from holding a rally,

only allowing a very controlled march during the Republican National

Convention. This time the hundreds of thousands of people attempting to

represent civil society and engage in their right to assemble were told we

would damage the grass on Central Park if we held a rally there on New

York's commons, where so many other events had been held through the years.

On another occasion more recently, a permit to march was only granted when

organizers threatened to march without a permit anyway. And what of the

100,000 or so people who protested the war in Afghanistan in Washington in

April, 2002? Or the 300,000 or so who protested the wars in September, 2005?

These were massive events, huge undertakings for many organizers and many

communities from around the country. Each person at each of these rallies

represents a hundred more who didn't make it. But they got a fraction of the

media coverage that this most recent one has received.

February 15th, 2003 and January 27th, 2007 will at least for some time be a

part of the memories of many people, including the media consumers who far

outnumber the many people who were actually in attendance. But for these

other equally massive outpourings of national discontent with the regime

that were hardly covered? If you weren't there, they may as well not have

happened. They do not enter into the national discourse any more than

current events in Micronesia.

And if this is how our right to assemble is dealt with, what of those

following the Gandhi-MLK tradition of nonviolent civil disobedience?

When people think of the WTO protests in Seattle in 1999, the popular

imagination is filled with images of young people dressed in black trashing

Starbucks and McDonalds in downtown Seattle. A couple hundred people

participated in this activity, and it has not been repeated to any

significant extent at any protests in the US since then. Most of the other

60,000 people protesting in Seattle miles away from downtown were being

drenched with tear gas for sitting in on the streets, nonviolently

surrounding the WTO meetings taking place in the Seattle Center. But as

usual, as soon as anyone started throwing rocks somewhere in town, this was

to be the media's primary focus.

Many people in the US feel in some way that everything changed after 9/11.

But in terms of a nation-wide campaign of disinformation and repression

against an activist community, the WTO protests were the bellwether event of

recent years. What had been local campaigns of various sorts against

rapacious corporations had grown into a nationwide (and already

international) movement against corporate globalization in general. The

corporate media responded with fear-mongering and disinformation, and the

authorities responded with repression.

For years after Seattle, the disproportionality of the reaction of the local

and federal authorities was at times comical. Anybody who was on the right

email lists leading up to Seattle knew it was gonna be big. Anybody on the

right email lists knew the protests at the IMF/World Bank meetings in

Washington, DC the following April (A16) was also going to be significant.

Anybody on those lists would also have known that the May 1st protests

calling for the shutting down of the Stock Exchange on Wall Street was going

to be small, but Mayor Giuliani was taking no chances.

The day began with what was being billed as a march for undocumented

workers. Several thousand Latino men, women and children marched, flanked by

what appeared to be almost an equal number of cops. As I recall, the cops

stood on either side of the march, two rows deep on each side. Most of the

cops were also about a foot taller than most of the marchers. These marchers

had a broad and thorough understanding of their role in this society. The

most popular sign on the march, in English, read simply "workers of the

world, unite."

This march was clearly never intended to be anything but a peaceful march

with no plans for civil disobedience. What was at some point intended to

follow the march was perhaps some kind of action, which I don't think had

ever gotten much beyond the planning stages, probably because most of the

organizers were too busy with A16, which had just taken place two weeks

before in DC.

In any case, to deal with the 200 or so anarchist youth who ostensibly

wished to shut down Wall Street, several thousand police were literally

tripping over themselves in the streets, which were awash with motorcycles,

paddy wagons, and bored cops feeling pretty stupid with nothing to do. In

preparation for the shutting down of Wall Street the cops had actually shut

down the entire business district around Wall Street, looking at the ID of

workers and residents wanting to cross police lines. Groups of police were

deployed to guard every nearby Starbucks or other corporate chain store, as

well as the World Trade Center and other places they thought might be

potential hotspots.

It was two weeks before then that police in Washington, DC had mass-arrested

600 or so people for daring to hold an unpermitted march. This happened in

the days leading up to the IMF/World Bank meetings, so the cops held

everybody over the weekend to keep them away from the protests.

On the first day of the meetings themselves, 20,000 or so people surrounded

the large area of town the police had walled off. The organizers of the

meetings had to bus delegates in during the wee hours of the morning, and

other delegates were stuck driving around the city for hours looking for a

way in.

Police behavior there didn't descend to the kind of wanton brutality of

Seattle, but I personally was walking past a group from Arizona who had

taken over one street, and witnessed an unmarked police van just drive into

and through the group. One man was on the ground. At first it was unclear

whether he was injured, but he had apparently gotten pushed to the side,

rather than underneath the van. The group quickly reassembled their line

afterwards.

That week in DC the police raided the main convergence center for the

protesters and confiscated all of the puppets and other artistic

representations people had been working on. They did the same thing in

Philadelphia a few months later leading up to the Republican National

Convention there in 2000. By the time of the Democratic National Convention

in Los Angeles, and given the well-deserved reputation for corruption and

brutality of the LAPD, the US Justice Department was actually involved with

overseeing the police for the occasion, and specifically ordered them not to

steal the puppets this time.

No event was too small or too large to warrant the hysteria of the corporate

media when it came to "anti-globalization" protesters. "The anarchists from

Seattle are going to come destroy the city." This was the mantra of the

corporate media in the weeks leading up to any protest for some time.

"Seattle anarchists" were the outside agitators of the day. Nowadays it's

"foreign fighters."

I think it was an anarchist book fair I was singing at in Bloomington,

Indiana around then. It was the sort of event in a small university town

that would a few years before have been considered quaint and very

Bloomington-esque. But now it was a cause for alarm, and for fear-mongering

about anarchists from Seattle, and maybe an excuse for the police department

to apply for federal grants to buy some new equipment.

When the anarchist youth took to the streets on bicycles in a fairly small

Critical Mass ride, the police took the occasion to strike, throwing young

people off of their bikes, handcuffing them and arresting them. I'm not sure

for what. Some kind of obscure traffic violation? Disorderly bicycling?

My concert was happening a half block from where the arrests took place, and

as usual, I was setting up to play, and not on a bicycle getting brutalized

and arrested. One young man came up to me and gave me a CD. "This is from my

friend," he said. "He was trying to come to your show, but he got arrested.

This was actually the third time he had been trying to go to one of your

shows but got arrested first." It was then that I was sure I was playing in

the right sorts of places.

The protests in Miami were a defining moment. By now it was 2003, two years

after 9/11. The "war on terror" and the war on "Seattle anarchists" had

merged. Miami's police chief, Timoney, had been responsible for the

brutality of the Philadelphia police during the RNC there, and now he was

police chief of Miami, in time for the FTAA (Free Trade Area of the

Americas) meetings and accompanying protests.

For weeks leading up to the protests, the Miami media was whipping up a

frenzy with talk about downtown being destroyed by anti-globalization

rioters from all over the Americas. Police Chief Timoney was showing videos

to the Miami police that were implying that police were killed during what

were increasingly being referred to as the "riots" in Seattle. By the time

we arrived, the cops were out for blood.

Downtown Miami was completely shut down, almost no businesses were open,

many were boarded up. The few businesses that were open were on our side.

The downtown exits on the highway were shut. Nobody was there but us, the

cops, and the media, who had mostly imbedded themselves fearfully behind

police lines.

Some of the cops and media were quite clearly afraid of us, which was

another one of those things that would have been really funny if it weren't

terrifying. Thousands of cops in riot gear, driving around in armored

personnel carriers, flying around in multiple helicopters circling overhead

at any given time, and they're afraid of 20,000 or so entirely unarmed

people, most of whom are fairly scrawny white college students...?

The scheduled events included a rally in an amphitheater, a march, and then

another rally back at the amphitheater. However, the cops decided not to let

more than 200 or so people into the 10,000-seat amphitheater for whatever

reason, either before or after the march. I managed to get in, and was, as

programmed, singing for the small crowd that was in there when the police

began their unscheduled, unprovoked assault on the demonstration outside.

I was doing a tour up the east coast immediately following the FTAA

protests, and it was like a gallery of wounds. Every town, every gig was

full of people who had been injured by the police in Miami. Here was one

friend with a big red splotch from being shot in the breast by a tazer.

Here's another with a hard lump the size of a baseball on his thigh from

being shot point-blank by a rubber bullet. Then the word that someone from

New Jersey died mysteriously days after inhaling too much tear gas. Those

"non-lethal" weapons again. By the time I got up to New York City I was

singing at a benefit for Indymedia there, who had gotten most of their

cameras taken by the police.

I was reminded of one visit to the Lower East Side in the '90s, during the

final siege of Tompkins Square Park by the police, to try to seize it along

with the rest of the neighborhood, to make it safe for gentrification. There

were garbage cans burning, crowds yelling and banging on things, overall it

was a very festive occasion. I remember seeing an older guy I knew as Uncle

Don there, and he had a broken arm. I asked him what he thought the

prospects were. "Too many people are getting their bones broken," he said.

"It can't keep going like this."

The blatant tactic is essentially to use overwhelming military force in

order to keep a social movement from getting too far off the ground. And

while these brutal and bizarre events receive gobs of local media attention,

they are virtually ignored by the national press.

Many thousands of people from all walks of life representing hundreds of

different organizations were pouring into the streets outside of these

various meetings of the corporate elites, and this was generally not

national news. If any national media might have considered covering the

protests in Miami, they scrapped those stories in favor of breaking news

having to do with Michael Jackson's nose, if I recall.

The local Miami TV stations were actual comedy, however. We were being given

a bird's eye view of scenes of the protests. We could see beneath us the

police attacking demonstrators, but the newscaster was saying things like,

"I think there's some kind of scuffle. The police are defending themselves."

Of course, we have the internet (at least as long as Congress maintains net

neutrality laws). We've got Pacifica Radio and many other means of reaching

people with useful information. But this kind of drumbeat propaganda on the

commercial and so-called public airwaves has a profound impact. It is still

a huge part of how most people find common reference points, common

understandings of broader reality, most of the time.

And what about just setting up a soapbox and speaking on the sidewalk? Well,

you're partially blocking a public walkway. Incredibly, I can tell you from

personal experience that in most places where people congregate in this

country, including on most subway platforms, you cannot sing a song with

your guitar case in front of you without being told to leave by the police.

The few places where it is legal to do this, such as Boston, it only became

legal after court battles over the First Amendment were won by the Street

Artists Guild in the 1970's.

I remember listening to BBC World Service a couple years ago. They were

doing a piece about street music being banned in Singapore. They obviously

thought it was a bit of an extreme measure on the part of the authorities

there. They joked that they liked the musicians playing in the London

Underground. Little did they know, evidently, that their own government had

banned music from the subway platforms a few years before, in 1995, as part

of the Criminal Justice Act. I remember it vividly, as it happened just

before the summer I was planning to make a living busking in the tube ...

It seems to me there's something to be said for knowing your situation. And

whatever happens, some things can be known. We've got freedom of speech,

sometimes. Every once in a while the media might even pay attention, though

most of the time they'll get it entirely wrong. And freedom of assembly?

We've got that sometimes, as long as you apply for a permit and actually get

one. Just make sure to move when they tell you to, if they give you time to

move after they tell you to. Otherwise you may be beaten and tortured with

"non-lethal" weapons. But usually they won't fire live ammunition. Viva

democracy!

David Rovics is a singer-songwriter who tours regularly throughout North

America, Europe, and occasionally elsewhere. His website is

www.davidrovics.com.

Tuesday, January 30, 2007

Mad About Mary - New York Times

The New York Times

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

January 30, 2007

Guest Columnist

Mad About Mary

By STACY SCHIFF

Once upon a time, asking about someone's children was like talking about the

weather. Then again, once upon a time talking about the weather was also

like

talking about the weather - not a portal into the political or the

apocalyptic. But that's another story. The point is that children made for

the kind

of paltry social currency you could exchange with your in-flight neighbor,

back when the only other option might have been: "As you're carrying that

knife

and wearing full camouflage, is it safe to conclude that the vegetarian meal

is mine?" Then came children as designer accessories and politically charged

pawns, appendages and admissions statistics.

Suddenly, we are on treacherous ground. For starters, Angelina Jolie and

Madonna can't even agree on where babies come from. I thrill as quickly as

the

next People subscriber to a good catfight, but do we really need Angelina -

who appears to have taken No Child Left Behind as her personal mantra -

trashing

celebrities for "jumping on the adoption bandwagon?"

As her swearing-in made clear, even Nancy Pelosi feels the need to

accessorize, not something I would have thought a woman with a gavel would

ever need

to do. Yes, by comparison the back of the House looked like a bouncer

convention. But the dais looked like a Sunday school class. Which raises a

parenthetical

question: Do female politicians have to kiss babies? For that matter - this

question is for someone other than Senator Boxer or Secretary Rice - do they

need to have babies?

There are now officially only two people left in America who don't want to

talk about their kids. When Jim Webb bowed out of that White House receiving

line, President Bush tracked him down and asked after his son. Senator Webb

is a former Navy secretary; he knows his protocol. He is also one of only a

few members of the U.S. Senate with children serving in the military. "I'd

like to get them out of Iraq, Mr. President," Mr. Webb replied. "That's not

what I asked you," Mr. Bush snapped. Mr. Webb didn't really mean to answer,

either. Evidently, he meant to slug the president.

Last week Wolf Blitzer asked Dick Cheney about his pregnant lesbian

daughter. The vice president looked as if his arm had made contact with that

meat grinder.

Mr. Blitzer was, he growled, seriously out of line.

Neither Senator Webb nor Vice President Cheney wins points for his social

graces. But what Letitia Baldrige said of the Webb encounter - "It was an

uncivil

reply to an uncivil remark" - does not apply equally to the vice president.

Mr. Cheney has openly promoted an anti-gay agenda. His own base has called

his daughter's pregnancy unconscionable. Family values have been his calling

card. And our Prohibitionist vice president can't summon the courage to

address

the gin mill in the basement?

Mr. Webb was rude on principle; Mr. Cheney rude out of hypocrisy. One man

took a stand. The other scurried away.

What the vice president's nonresponse did deliver was a very cogent message:

the rules apply to you, but not to us. It's our privacy, your patriotism;

our

delusion, your sacrifice; our tax cuts, your kids. After all, as Mr. Cheney

so tellingly said of his Republican critics, "I'm the vice president, and

they're

not." The part for which some of us have no stomach is the sense of

entitlement.

An annoying thing about children is that they nudge you toward the high road

and the long view. They demand pesky things like open-mindedness,

self-denial,

accountability, leadership and occasionally even integrity - qualities that

appear to have packed up and gone home with Hans Blix. Once upon a time, you

might have termed them family values.

So as to spare Mr. Cheney any further misadventures in this minefield, I did

a little research for him. Several years ago, Ms. Baldrige foresaw his

predicament.

"A lesbian's parents may be the victims of probing, mean questions from

their friends," she wrote. "Hopefully, they will answer unequivocally that

they

stand by their child and accept her decision."

As for gay and lesbian couples, they are families, too, in Ms. Baldrige's

book. They are also increasingly common, "so people who feel shy and uptight

with

them are just going to have to get over it." Alternatively, they are welcome

to talk about the weather.

Stacy Schiff is the author, most recently, of "A Great Improvisation:

Franklin, France and the Birth of America." She is a guest columnist.

Posted by Miriam V.

Reporter defeats gov. intimidation

By Evan Derkacz

AlterNet, Posted on January 30, 2007

http://www.alternet.org/bloggers/evan/47411/

Sarah Olson, the independent journalist who interviewed Lt. Ehren Watada, an

officer who refuses to deploy to Iraq, took a stand when the U.S. Army began

to use her interview to build its case against him, even subpoenaing her to

testify.

On AlterNet recently, she wrote: Among multiple issues this raises, the

circumstance begs a central question: Doesn't it fly in the face of the

First Amendment

to compel a journalist to participate in a government prosecution against a

source, particularly in matters related to personal political speech?

The intention is obvious. In the case against Lieutenant Watada, the U.S.

Army is attempting to use a journalist as an investigative tool for their

prosecution.

In this case, the journalist is me. And I wholly object to this attempt at

eliciting my forced and unconstitutional participation.

Yesterday, the Honolulu Advertiser reported that the government has dropped

two of the charges against Watada, who agreed upfront to all the questions

that

would've been asked to Olson.

Olson, who will no longer have to testify, wrote:

This is obviously a great victory for the principles of a free press that

are so essential to this nation. Personally, I am pleased that the Army no

longer

seeks my participation in their prosecution of Lieutenant Watada. Far more

importantly, this should be seen as a victory for the rights of journalists

in the U.S. to gather and disseminate news free from government

intervention, and for the rights of individuals to express personal,

political opinions

to journalists without fear of retribution or censure. I am glad the growing

number of dissenting voices within the military will retain their rights to

speak with reporters. But I note with concern that Lt. Watada still faces

prosecution for exercising his First Amendment rights during public

presentations.

However, the preservation of these rights clearly requires vigilance.

Journalists are subpoenaed with an alarming frequency, and when they do not

cooperate

they are sometimes imprisoned. Videographer Josh Wolf has languished in

federal prison for over 160 days, after refusing to give federal grand jury

investigators

his unpublished video out takes. It is clear that we must continue to demand

that the separation between press and government be strong, and that the

press

be a platform for all perspectives, regardless of their popularity with the

current administration.

Evan Derkacz is an AlterNet editor. He writes and edits PEEK, the blog of

blogs.

Gathered by Sylvie K

Posted by Miriam V.

Yes, I’m Listening to Kerry

Yes, I’m Listening to Kerry By Marie Cocco

WASHINGTON—Not long after the “botched joke” blew that gaping hole through John Kerry’s political ambitions, I called a Democratic friend and made a promise: I will never, ever, say anything nice about Kerry again.

Promise made, promise broken.

Within a few days, Kerry is to offer the Senate yet another chance to consider what always have been his well-informed—and often wise—ideas for how to manage the disaster that is Iraq. The media shorthand will be that Kerry calls for “withdrawal.” The Massachusetts senator is, indeed, working on a measure that will most likely set deadlines for redeploying American troops and outline a diplomatic thrust that is so urgently and obviously needed to quell a civil war that threatens to become a regional conflagration.

It is worth noting that when Kerry proposed a similar approach last June, most of the political commentariat ridiculed him as pandering to antiwar activists, a supposedly crucial bloc of support needed for a 2008 Democratic presidential run. Kerry’s resolution went down by a vote of 86 to 13. Republicans were still echoing White House talking points that ridiculed all alternatives as “cut and run.” Most Democrats were still cowering.

Now, having given up his dream of becoming president, Kerry is more public servant than politician. He has reached down inside to tap that same quality that led him to volunteer for duty in Vietnam when others of his social status found safe havens from the fight. It is the same impulse that led him to win medals for his valor, the same courage that led him to return home to protest a dirty war when he could have tucked away his medals and marched off to law school.

It is, in fact, a quality we are always saying we want in a president: character.

The prospects for a second Kerry presidential bid were poor, and this was painfully obvious. The prospects for a winning vote in the Senate on firm deadlines for redeploying the American forces besieged in Iraq are, in all likelihood, equally bleak. Senators from both parties bicker instead over the wording of nonbinding resolutions expressing varying degrees of displeasure with President Bush’s decision to send in more troops. Should the Senate “oppose” the president’s policy, or merely “disagree”?

No matter. Bush will ignore them. All senators know it. This is the heart of our national political crisis.

It has now been 14 months since Rep. John Murtha, D-Pa., the defense hawk who supported the 2002 resolution that authorized the Iraq invasion, called Bush’s approach in Iraq “a flawed policy wrapped in illusion.” Is it now less flawed, less shrouded beneath the illusions that envelop the White House?

More than two years have passed since Kerry first outlined, as part of his presidential bid, a regional diplomatic initiative to involve Iraq’s neighbors. Its goals would be to keep Iraq’s borders intact, prevent outside interference in Iraq’s internal affairs and protect its minorities. Last fall, the bipartisan Iraq Study Group endorsed the same approach.

Who can say whether Kerry’s new redeployment plan will set the right course out of Iraq? There is no risk-free way to extricate ourselves from this bloody folly. We can be more certain that President Bush will continue to stumble ahead, sacrificing American and Iraqi lives on the pyre of his determination to avoid responsibility for defeat.

As for Kerry, we no longer have to worry about his windsurfing or the size of his wealthy wife’s investment portfolio. The idiotic discourse that consumed the media during the 2004 presidential campaign is exposed, fully and tragically, as the bread and circuses of our day. The diversions were more than the smearing of an honorable man. They were disastrous for the country, for they blinded so many to what already was a deepening state of chaos in Iraq.

Now that we have no particular reason to listen to John Kerry, will we?

Certainly we should. The attentiveness should begin in the Senate, where Kerry announced he would not seek the presidency and returned instead to his political roots as an unconstrained opponent of a failed war. He reminded his colleagues of what they all know and have refused thus far to admit: “The mistakes of the past do not change the fact that Congress bears some responsibility for getting us into this war and, therefore, must take responsibility for getting us out.”

The Black Gold Rush: Divvying Up Iraq's Oil

A reform law put together with lots of help from U.S. consultants could finally open Iraq's massive reserves to Big Oil. James Ridgeway, Mother Jones•

MoJo:

Thirty years ago, early neocons created a plan for U.S. control of Persian Gulf oil. Now it's playing out.

The president's decision to use force against Iranian "agents" inside Iraq could snare innocent pilgrims, and raises the risk of open warfare.

By Juan Cole

George W. Bush last week announced that American troops in Iraq were henceforth authorized to "kill or capture" any Iranian intelligence agents they discovered in Iraq. The announcement came on the heels of his pledge in the State of the Union address to bring another aircraft carrier into the Persian Gulf, a move that clearly targeted Iran. A prominent Iranian parliamentarian responded to Bush's threat by saying, "Such an order is a clear terrorist act and against all internationally acknowledged norms." Iraq's deputy prime minister, meanwhile, put a pox on both Iran and the U.S. for conducting their geopolitical battle on Iraqi soil.

The danger of Bush's approach may be realized in short order. Tuesday, Jan. 30, marks the 10th day of Muharram, and is the Islamic holy day known as Ashura. Iraq is the Shiite holy land, the site of the passion and martyrdom of revered figures such as Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammed, and al-Husayn, the Prophet's grandson. Thousands of Iranians come on pilgrimage to the Shiite shrine cities of Najaf and Karbala in Iraq every year, and the flow of pilgrims peaks at Ashura, which commemorates the martyrdom of al-Husayn. Ashura is an especially important holiday to Shiites, drawing up to 1 million pilgrims to Karbala, 60 miles southwest of Baghdad. In 2004 Sunni insurgents exploited the presence of so many Shiite pilgrims by setting off massive explosions that killed more than 100 people.

Given Bush's new directive, how will U.S. troops distinguish between innocent Iranian devotees and spies? What if U.S. troops kill pilgrims in a mistaken belief that they are covert operatives? Leaving aside whether U.S. law authorizes such a broad, vague use of deadly force against foreign nationals, which is unclear, Shiite religious sensibilities would be inflamed in both Iraq and Iran, furthering the potential for a widening conflict.

Or maybe the spark for a wider conflict is just what the increasingly desperate President Bush seeks. His fixation on Iranian activities in Iraq cannot be explained by his cover story, which is that Tehran is supplying weapons to forces that kill U.S. troops. To date, no hard evidence that the Iranian government is sending high-powered weaponry into Iraq has been made public, and no credible proof may be forthcoming. In general, one should take such claims with a large grain of salt, much like the skepticism with which one should greet the official U.S. story about the firefight in Najaf on the weekend that supposedly claimed the lives of 250 insurgents.

To begin with, some 99 percent of all attacks on U.S. troops occur in Sunni Arab areas and are carried out by Baathist or Sunni fundamentalist (Salafi) guerrilla groups. Most of the outside help these groups get comes from the Sunni Arab public in countries allied with the United States, notably Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies. Washington has yet to denounce Saudi aid to the Sunni insurgents who are killing U.S. troops.

Meanwhile, the most virulent terror network in Iraq, which styles itself "al-Qaida in Mesopotamia," has openly announced that its policy is to kill as many Shiites as possible. That the ayatollahs of Shiite Iran are passing sophisticated weapons to these, their sworn enemies, is not plausible.

If Iran is providing materiel to anyone, it is to U.S. allies. Tehran may be helping the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq and its Badr Corps paramilitary, but the U.S. is not fighting that group. By sale or barter, some weaponry originally given to the Badr Corps might be finding its way to other groups, such as the Mahdi Army of nationalist Shiite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, that do sometimes come into conflict with the U.S. That problem, however, must be a relatively small one, and cannot explain Bush's hyperbolic rhetoric about Iran.

Some of the reports of "thousands" of Iranian agents in Iraq come from the Mojahedin-e Khalq terrorist group, which is made up of Iranian expatriates who display a cultlike devotion to their leader, Maryam Rajavi. An enemy of Tehran, responsible for numerous bombings inside Iranian borders, the MEK was given a terrorist base, "Camp Ashraf," in eastern Iraq by Saddam Hussein. When the U.S. invaded Iraq, some Pentagon figures wanted to use the MEK against Tehran in the same way Saddam had, and the MEK fighters have not been expelled from the country. They now supply disinformation about Iran to the U.S. in order to foment conflict, much as Ahmad Chalabi lied in order to sell the Americans on invading Iraq.

That the U.S. is in search of a rationale for a wider conflict is supported by the fact that it has arrested Iranian officials inside Iraq on two occasions in the past six weeks. In December, U.S. troops raided the compound of Shiite cleric Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, the leader of the largest bloc in parliament, made up of fundamentalist Shiites, and discovered several visiting Iranians there. Some were briefly detained and then allowed to leave the country. Two others were delivered to Iraqi government custody and accused of being high-ranking intelligence officers of the Quds Force unit of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Force. Baghdad at length let them go, as well.

Al-Hakim, as well as Iraqi President and Kurdish leader Jalal Talabani, indignantly insisted that they had invited the Iranians to the country, protests that seem strange if the Iranian visitors were harming Iraqi interests. Press reports on the documents the U.S. captured in the raid were contradictory. American newspapers said that they indicated Iranian arms smuggling and included plans for ethnic cleansing of Sunnis in Baghdad. British intelligence officials told the BBC, in contrast, that the documents did not mention arms but indicated that the Iranians had come to consult about the cabinet shuffle planned by Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, head of the fundamentalist Shiite al-Dawa party, the largest bloc in the legislature.

The U.S. then launched a raid in the far northern Kurdish city of Irbil on an incipient Iranian consulate, there by the invitation of the Kurdistan Regional Government. Troops captured five Iranians, which the U.S. accused of being intelligence operatives. Again, the Iraqi Kurdish officials expressed annoyance and affirmed that the paperwork had been submitted for the establishment of the consulate.

There are very few U.S. troops in the northern Kurdish regions, and the Iraqi Kurds are close allies of the United States. How Iranian activities in Irbil could possibly pose a threat to American troops is completely mysterious. Why Washington would order arrests of persons designated as guests by Iraqi government officials is also obscure.

Maybe what is really going on is that the Bush administration finds itself competing with Iran for influence with erstwhile allies in Iraq and losing. Abdul Aziz al-Hakim was feted at the White House on Dec. 4 of last year and said he wanted U.S. troops to remain in the country. His contacts with Iranian officials, whether intelligence operatives or not, pose no military threat to the U.S., since he is a Bush ally. They might, however, pose a political threat insofar as al-Hakim's Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq can act with more independence from Washington if it receives aid from Tehran. At the invitation of the Iraqi government, Iran has now offered to expand its economic presence in Iraq.

As Washington grows weaker in Iraq, it is concerned that Iran not pick up the pieces and establish hegemony over its smaller neighbor. The Bush administration may also be casting about for some issue that will galvanize the American public and give it a pretext to expand its presence in Iraq despite how badly the war has gone. Any leaders of a failing war effort are always tempted by a strategy of escalation. Announcing open hunting season on all Iranian visitors to Iraq is like playing Frisbee with nitroglycerin. Bush has gone looking for trouble and is likely to find it.

by Sen. Russ Feingold

For the first time in the four-plus years since Congress authorized the Iraq war, Congress is having a serious debate about how we can fix the President's failed Iraq policy. Unfortunately, while there have been plenty of members of Congress, both Republicans and Democrats, voicing opposition to the President's plans for escalation, most of the plans being pushed will do nothing to end the catastrophe in Iraq.

Americans are not looking to Congress to pass symbolic measures, they are looking to us to stop the President's failed Iraq policy. That is why we must finally break this taboo that somehow Congress can't talk about using its power of the purse to end the war in Iraq. The Constitution makes Congress a co-equal branch of government. It's time we start acting like it. We have a moral responsibility, as well as a responsibility to the brave troops whose lives are on the line, to end the war. We can and must force the President to safely redeploy our troops so that we can get back to focusing on those who attacked us on 9/11.

Tomorrow, I will be chairing a full Judiciary Committee hearing entitled "Exercising Congress's Constitutional Power to End a War." This hearing will help remind my colleagues in the Senate and the American public that Congress is not powerless - even when it acts that way. We have the power to stop the policies of a President that continue to hurt our national security. Soon after tomorrow's hearing, I will introduce legislation to do just that.

I want everyone to be clear on exactly what my proposal will do. The first and most important thing to know is that my plan does not cut funding for the troops. Our troops will continue to receive the salaries, equipment, training and protection they need. What I am proposing is ending funds for the continued deployment of U.S. forces in Iraq six months after the enactment of the bill. This will require the President to safely redeploy troops from Iraq by that date. My bill does provide exceptions to allow for specific types of military missions within Iraq past the six-month deadline, such as targeted counter-terrorism efforts, the protection of American personnel and infrastructure, and a limited number of troops needed to help train Iraqi security forces. But these will be limited forces used for specific missions.

Suggestions that our troops will be left in the lurch couldn't be further from the truth. My proposal would bring the troops out of harm's way.

Congress has used this power several times before, most recently in Somalia and in Bosnia in the 1990s. Nevertheless, I'm sure the White House and others will resort to their usual intimidation tactics to try to paint this proposal as not supporting the troops. I'd like to hear from the President exactly how sending 21,500 more U.S. troops into a civil war supports them. We must not let this administration continue to intimidate like it did in the lead-up to war.

In August 2005, I became the first Senator to propose a timetable for the redeployment of our troops from Iraq. A timetable was considered taboo in Congress then, but it's clearly the position supported by the majority of this country. Now it is time to break another taboo - that Congress can't use its constitutional power to end funding for the war and bring our troops home safely. The catastrophe in Iraq is not the fault of our brave men and women in uniform, but rather the failed policies of this administration. Our troops and our national security should no longer be the ones to suffer for this Administration's terrible mistake.

Monday, January 29, 2007

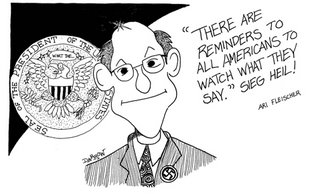

Fleischer: Libby told me about Plame "on the q.t."

Fleischer: Libby told me about Plame "on the q.t."Scooter Libby told Patrick Fitzgerald's grand jury back in 2004 that he first learned that Joseph Wilson's wife worked for the CIA when Tim Russert told him as much on or about July 10, 2003.

Ari Fleischer says it's not so.

Testifying this morning in Libby's perjury trial, Fleischer said that Libby told him on July 7, 2003, that Wilson was sent to Niger by his wife and that his wife worked in the counterproliferation division of the CIA. "I think that he told me her name," Fleischer said.

Fleischer said that Libby told him the information was "hush-hush" and "on the q.t." He said he didn't know what Libby meant by that, but he interpreted it -- see if you can follow this -- as meaning that the information was "kind of newsy."

Fleischer seemed nervous as he took the stand -- indeed, he was nervous enough that he insisted on getting immunity before answering questions in front of Fitzgerald's grand jury -- but he warmed to the job after a few minutes, describing events at the White House in the mildly condescending manner of a tour guide talking to a school group: The press secretary speaks for the president and has "all sorts of meetings with reporters"; the State of the Union address is a "very important event" where the president can "define what he seeks to do"; in the White House basement, there are "two messes" where staff members can meet and eat.

Fleischer said it was over lunch in one of those messes that Libby first told him about Wilson's wife. Wilson's New York Times Op-Ed was one of three subjects of conversation that day, Fleischer said. The other two? Fleischer's future -- he had already announced that he was leaving the White House -- and the Miami Dolphins.

Fleischer: Plame news was a "so what" for reporters

Ari Fleischer on what happened when he told a handful of White House reporters traveling with the president in Uganda that Joseph Wilson's wife had sent him to Niger: "The press's reaction was, 'So what?' They didn't take out their notebooks, they didn't start writing anything, they didn't ask me any follow-up questions as I recall ... Like a lot of things I said to the press, it had no impact."

Fleischer said it was a bit of a "so what" to him, too. While Fleischer said he thought that the claim that Wilson's wife sent him to Niger helped bolster the White House's defense that Dick Cheney didn't send him there -- and, hence, the White House shouldn't know what Wilson found there -- he said he didn't think "in my wildest dreams" that he was leaking classified information to the press or that he'd someday read in the newspaper that Valerie Plame was a "covert agent in the Central Intelligence Agency."

That part is a bit of a "so what" to Libby's lawyers, who leapt to their feet to object lest the jury infer from Fleischer's testimony that Plame was, in fact, a "covert" CIA agent. After a brief sidebar with the lawyers, Judge Reggie Walton instructed the jurors that they were not to infer anything about Plame's status at the CIA based upon what Fleischer had said.

A few minutes later, Fleischer testified that he first realized that he might be in "big trouble" for leaking Plame's name when he read in the New York Times that the CIA had asked for a criminal investigation into the leak.

The unflappable Ari Fleischer?

Scooter Libby defense lawyer William Jeffress has spent much of the afternoon trying to chip away at the credibility of Ari Fleischer. It wouldn't seem to be a particularly difficult task: As White House press secretary, Fleischer dissembled on everything from Iraqi WMD to the president's views on nation building to the threats that weren't made against Air Force One on 9/11.

But on the more narrow matter at issue today -- what Libby told Fleischer over lunch in the White House mess on July 7, 2003 -- Jeffress hasn't yet landed much of a punch. Fleischer testified earlier today that Libby told him during that lunch that Joseph Wilson had been sent to Niger by his wife and that Wilson's wife worked in the counterproliferation division of the Central Intelligence Agency. If the jury believes Fleischer, his testimony is a major blow for Libby, who said, in sworn testimony before the grand jury, that he first learned about Wilson's wife from Tim Russert three days later.

Jeffress hasn't accused Fleischer of making up the lunch conversation, exactly, but he has tried mightily to nibble around at the edges. Fleischer hasn't given much ground, leaving Jeffress' inquiries to land with dull thuds rather than the explosions he might be intending.

Jeffress seized on the fact that Fleischer had said he thinks -- rather than he knows -- that Libby used Valerie Plame's name during their lunch. "That's what you say, 'I think,' on the name." Yes, Fleischer said: "I said 'I think.'" You don't know for certain? "Absolute certainty? No."

Jeffress noted that Fleischer had pronounced Plame's name two different ways in his grand jury testimony -- once as if it rhymed with "flame," another time as if it were pronounced "Plaw-may." Doesn't that suggest that Fleischer first learned of Plame's name by reading it somewhere rather than by hearing someone say it? No, Fleischer said, explaining that while it mattered to him that Wilson's wife worked at the CIA -- he thought it helped back up his claim that the Office of the Vice President hadn't sent Wilson to Niger -- he really didn't care what her name was.

Jeffress noted that Fleischer testified that he had talked with Libby about the Miami Dolphins during their lunch. In what seemed like an attempt to prove that Fleischer didn't really have such a clear independent memory of the discussion, Jeffress asked Fleischer to read a "goodbye and good luck" letter he received from Libby a few days later -- a letter in which Libby mentioned their mutual affection for the Dolphins. Jeffress didn't follow up, apparently thinking that he'd made whatever point he meant to make. Maybe he had, but the result was more lightning bug than lightning.

Jeffress reminded Fleischer of a conversation he had with NBC's David Gregory in which Gregory said it was too bad that Fleischer had to deal with the controversy over the "16 words" in Bush's State of the Union address during his last week as White House press secretary. Fleischer told Gregory that it was all the same to him -- that if it hadn't been "this crap" it would have been "some other crap." Didn't Fleischer call Gregory and ask him not to quote him on that? Yes, Fleischer said. Why was that, Jeffress asked. "Because," Fleischer said, "I don't think press secretaries should go around using that word."

It might be too much to say that Fleischer is unimpeachable, but a man who spent two and a half years defending George W. Bush is a man who can handle himself on cross-examination -- especially when he's sporting the well-dressed, well-fed look of a corporate communications consultant and packing a grant of immunity in his pocket.

And now, a few words from David Addington

With the lawyers having finished with Ari Fleischer, David Addington is now on the witness stand at the Scooter Libby trial. It's late in the day, and either Addington is the most talkative person in the world -- an odd character trait for Dick Cheney's chief of staff -- or he's just trying to run out the clock before getting to matters of substance tomorrow.

Addington spent what seemed like a lifetime describing his work experience. He described -- by approximate dimensions and also by comparison to a table in the courtroom -- the size of an office in the West Wing. He painted a word picture of the seating arrangements on Air Force Two: which seats are on the "port" side, which seats are on the "starboard" side and who sits in each. He offered excruciating detail about procedures the White House might use to gather documents requested by the Justice Department.